Tonight I saw the documentary film

Highway Courtesans, a

Women Make Movies Release, on DVD. It is about the

Bachara tribe in the western part of

Madhya Pradesh in central

India. This tribe is known for the tradition of child prostitution, with families making their first daughters, as children, into

prostitutes to support the family. The tradition is centuries old and is still practiced today.

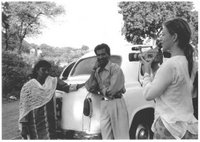

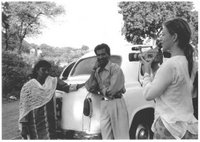

The film, directed by

Mystelle Brabbée, follows six years in the life of Bacharan Guddi Chauhan from age 16 to 23. She has been a prostitute serving passing-by truckers and others I believe since age 11 or 12, but clearly is uneasy about this forced occupation. Along the way, she has garnered a boyfriend, Sagar, out of her clientèle. Sagar surprisingly seems not to mind her profession.

Guddi's misgivings lead her, against her family's wishes, to leave prostitution and learn enough to become a teacher in a village.

How do her drunken do-nothing brother and tradition-bound father react to her independent streak? How does Guddi, as well as some of her peers in the community, Shana and Sungita, feel about the tradition and the role thrust upon them? Change is often a two-edged sword, and would fighting this tradition benefit these young ladies and girls? What other opportunities exist, where do they exist, and do ex-Bacharan prostitutes have hopes of marriage? Can they fulfill their desires to support their families? Why is Sagar vague about his plans to marry Guddi? We see Guddi's father sending her by bus to a larger town to get a proper education; will he support her and let her study?

This 71-minute film that took approximately ten years to produce gives insight into these questions. It is difficult to come to terms with forced child prostitution, especially in modern times, and a documentary on this topic could leave one numb. Instead, the film is crafted in an accessible and warm manner. The prostitutes are victims, but somehow Guddi, Shana, and Sungita, are surprisingly strong and confident.

I am impressed with the access that the filmmakers were able to get to the people in the Bacharan village, and to the villagers' willingness to frankly discuss matters. By clearly documenting this story, the producers have used film to possibly make a big difference in the lives of these highway courtesans. But will this age-old tradition become a thing of the past? And if it does, will reasonable opportunities for villagers be available? We can only hope.

Highway Courtesans

has won a number of awards, such as best feature documentary at the 2005 Galway Film Fleadh and winner of the President's Jury Award at the 2005 Chicago International Documentary Festival. I understand that it is set for theatrical release this November at New York City's Quad Cinema in Greenwich Village. Established in 1972, Women Make Movies, the film's distributor, is a national non-profit media organization and the largest distributor of films made exclusively by and about women. WMM's collection of more than 500 films are used by thousands of educational, community and cultural organizations annually, exhibited at film festivals worldwide and broadcast on television and cable stations in the U.S. and abroad.Links of interest:

Photographs used with permission courtesy of Women Make Movies (www.wmm.com): Guddi as teacher, trucks on Ratlam Highway, view outside Guddi's home, Guddi with her boyfriend Sagar and director Mystelle Brabbée.

Photographs used with permission courtesy of Women Make Movies (www.wmm.com): Guddi as teacher, trucks on Ratlam Highway, view outside Guddi's home, Guddi with her boyfriend Sagar and director Mystelle Brabbée.

Tonight the NC Museum of Art's summer lawn series featured the original Japanese Godzilla (Gojira; Ishiro Honda, 1954; not the 1956 American version with Raymond Burr). I enjoyed it ... more writeup coming soon ...

Tonight the NC Museum of Art's summer lawn series featured the original Japanese Godzilla (Gojira; Ishiro Honda, 1954; not the 1956 American version with Raymond Burr). I enjoyed it ... more writeup coming soon ...